Introduction

The use of drones, whether for reconnaissance or for search-and-destroy missions, in military operations no longer raises eyebrows, thanks to their widespread use in the on-going conflict in Afghanistan; although the collateral damage caused by the latter category of missions still raises ethical concerns about accountability and culpability.

2011 saw the increasing use of drones by law-enforcement agencies (LEAs) for law and order activities, in the United Kingdom and the United States of America. The year also saw the first steps being taken, by private organisations and groups, in the use of drones for reconnaissance and information-gathering purposes. This brief examines the implications of the use of drones, by LEAs and private parties, on Homeland Security.

Types of Drones

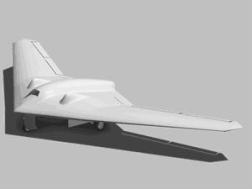

When the word drone is used, the image that pops up is of a sophisticated, futuristic-design based platform supporting an array of sensors and weapons: like the Predator or the Sentinel, both of which have been operating in Afghanistan.

|  |

| Figure 1: Image of the General Atomics MQ-1 Predator (left) and an artist’s rendering of the Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel (right) Credit: Wikipedia | |

Outside the military, drones like the Predator have seen use by agencies such as the FBI and the DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration), in the USA, for local operations. So far, police authorities in the USA have been barred from using drones on account of FAA (Federal Aviation Authority) regulations that restrict such use in domestic airspace; but those regulations are expected to see an amendment this year, permitting police drones.

In the UK, police authorities have been using drones since 2007, for video surveillance activity, although these drones have been of a far simpler design and of limited capability. The fact of the matter is that there are low-operating infrastructure drones available, which allow LEAs to own and operate drones without large Capex and Opex budgets. A category of drones, called Micro Air Vehicles (MAVs) are bringing aerial reconnaissance capabilities to any agency with a Capex budget of between Rs. 25 – 35 Lakhs.

|  |

| Figure 2: Image of the Honeywell’s T-Hawk Micro Air Vehicle (left) and a helicopter-design based UAV (right) Credit: Honeywell Aerospace www.thawkmav.com, for the image on the left | |

MAVs can range in size from as small as 15 cm. to the size of a large model airplane; with capabilities ranging from carrying out reconnaissance and surveillance to engaging in offensive action using non-lethal weapons (stun guns, audio amplifiers, strobe-lights, etc.); and capable of carrying payloads ranging from a few 100s of grammes to a couple of kilogrammes. They can be hand-launched or launched from a compact launch platform, depending on the size of the platform, and can be airborne for anywhere between a few minutes to an hour: covering an area of a radius of between one kilometer and over 10 kilometres. Finally, the skills required to operate an MAV are not hard to impart and refine, facilitating its use among non-specialised operators.

Use of Drones by LEAs in India

A couple of earlier Tech. Briefs – Sensor Delivery Platforms (October 2010) and IEDs in Insurgency and the Use of Technology in Their Detection (July 2011) – touched upon the use of UAVs for Homeland Security requirements, mainly for anti-insurgency operations.

The case for police authorities in India using surveillance/reconnaissance drones is compelling, once a strong regulatory framework is put in place. One of the main advantages of a drone, in functions such as surveillance and reconnaissance, is that it manages to collect information covertly or from a safe distance; invaluable benefits when trying to track a suspect or when trying to control a mob. The nature of the information collected will depend on the sensor payload of the drone, and this flexibility can be leveraged to utilize a drone for anything from video surveillance (day or night), to eavesdropping, to trace detection. Given the advantages, with respect to cost and ease-of-operation, of the MAV form-factor, it is this UAV that will be best suited for LEA duties.

An LEA looking at owning and operating an MAV will need to firm up operational requirements in few areas before deciding on a solution:

- Drone Characteristics

The user has to decide on its requirements for the operating range and altitude for the drone, endurance, payload size and weight, and launch space. Fixing values on these parameters will allow the user to shortlist drones that will be capable of delivering against user missions. - Sensor Payloads

The user has to decide on the types of sensors it will like the drone to carry, either singly or in combination. Typical sensor payloads for LEA type of requirements are daylight and IR video surveillance cameras, audio eavesdropping, trace detectors (explosives and gases), SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar), electronic eavesdropping, and image intensifiers. In addition, the user will need to decide whether it wishes to have the sensor payloads as detachable pods or as permanently fitted. - Operations Base

Given that all drones have an upper limit with respect to range and endurance, it is always preferable to launch the drone as close to the area of operation as possible. Given this preference, the user will need to decide on what is going to serve as the Operations Base for the drone: is it going to be a Mobile C4ISR vehicle, or the closest secured facility (e.g. police station), or any public space large enough to allow the drone to be launched? Accordingly, the support team for operating the drone will need to be able to reach the Operations Base in quick time. When operating MAVs, it is preferable to use a mobile platform as the Operations Base. - Monitoring Base

Where does the sensor data-stream go? The Monitoring Base is the facility that receives the sensor streams and analyses the data for actionable information. The Monitoring Base can either be at the same location as the Operations Base, thereby reducing the time lag between capturing and receiving the sensor data-stream. Alternatively, if the number of drones is large, it can be a dedicated Command & Control centre with specialized analysts and senior decision-makers.

Potential Abuses

The earlier section briefly touched upon the need for a strong regulatory framework, before drones are deployed for domestic law enforcement functions. The first step would be to get the necessary amendments from the DGCA (Directorate General of Civil Aviation), allowing use of Indian airspace by UAVs operated by LEAs.

The next step would be to set up structures and processes covering the operation of such UAVs, with the objective of preventing potential abuses of the technology. The issues arising from the use of drones are, to a large part, the same as those arising from the use of any surveillance: privacy of citizens, the confidentiality of the data captured by sensors, and the secureness of the any such data repository.

However, a couple of issues have significantly greater implications in the case of drones, than in the case of fixed surveillance sensors:

- Identifying an MAV and its Operator:

Given the mobile nature of MAVs, and their design for covertness, it is important to set up a process, within each LEA and at the national level, for operating an MAV. The process needs to cover the ability to identify an MAV when it is in flight (through the use of an identification transponder), the ability to identify the operator (through unique user IDs) during an operation, and the ability to review any footage captured by the MAV at a later point in time. Such a process is a must to address the issue of an LEA drone being misused, by rogue elements in the LEA, for illicit assignments. - Hacking:

Drones, being self-contained, sentient devices, are more susceptible to hacking than dumb sensors or basic-intelligence sensors. Although any electronic equipment is susceptible to hacking, the implications of hacking a drone are more serious than that of a surveillance camera or any other fixed surveillance sensor. Iran recently brought down a US drone, operating in Iranian airspace, by jamming the link between the drone and its command, and then feeding the drone false co-ordinates in order to get it to land in Iran. While hacking a sensor will typically result in the sensor sending its data-stream to the hacker; in the case of a drone, the hacker can deploy a hacked drone for operations on targets that it wishes to keep under surveillance. - Use of drones by private entities:

Once LEAs are authorized to use drones, there is nothing to stop private entities, from doing so too; given the relatively simple operational requirements of MAVs. Today, with drones being banned for domestic (non-insurgency) law and order situations, it is always evident to an LEA that if a drone is spotted, it must be illegal. However, once an LEA is allowed to deploy drones for domestic law and order situations, there is no way a policeman will be able to differentiate a legitimately-operated drone from an illicitly-operated drone. Private organisations are already deploying drones, internationally, as evidenced by the use of one by an anti-whaling group, Sea Shepherd, to keep a track of Japanese whaling fleets. It is just as likely that drones are already being used, by private entities, in India today, with authorities not even being aware of the same. If so, the scale of the problem is going to increase manifold once permission is given to LEAs to own and operate drones. Provided there is a process in place to identify legitimate use, LEAs need to build the capability to bring down drones identified as illegitimate.

Conclusion

While there is a strong case for LEAs in India owning and operating drones, the move should be well thought out and backed by a strong regulatory framework; otherwise, more than in the case of other surveillance gear, the scope for misuse is significant.

Mistral offers the Mobile C4ISR platforms offering different levels of C4ISR capabilities to Homeland Security agencies. MAVs can be integrated in the larger Mistral Mobile C4ISR platforms, thereby providing more surveillance and reconnaissance teeth to LEAs using these platforms.